Late last August, a Sunday of the bank holiday I jump on a bus replacement service to Birmingham for a music festival. There’s something giddy about it all. I had bought my ticket the day before. Last minute chase to catch a lively curation of folk music.

Midway through the programming, Oxn, a side project of the group Lankum, play a hazardous set in which the bass player asks the sound engineer to increase the vocal in the monitors. He does a hand gesture for vocals; his thumb clapping his fingers like a crocodile sock puppet.

Nothing audible changes until the bassist unleashing a strum that hangs in time (2-3-4, 1-2-3-4), rendering the air heavy and imposing. The loudness. It breaks the gentle lullaby and vocal duet, wilting and falling. The drones of the keys collapse behind the explosion. Why it is still playing. Why is it not cut off. Why would it still play out.

The crowd cracked with laughter at the technical error and the shock. The way the performance had fallen apart. A comedian would have stopped and acknowledge what had happened, but the band continue, composed and defeated.

The bassist’s reaction – laughter and hiding behind equipment – seemed almost childlike, a giddy sugar-fuelled jump.

The sound technician seemingly misunderstood the request, or accidentally, turned up the wrong channel. According to the venue, “The issue was caused by the band not being able to hear the keyboard accompanying the vocal, a technical issue which once remedied caused the peak on stage and in the hall.”

I heard somewhere that bassists who get drunk are a sound engineers’ nightmare. Alcohol leaves the ear canals swollen and restrict our ability to hear low frequencies. So they turn up the gain and overdrive the sound into the red and distort the notes. It wasn’t his fault, but I look accusingly at the incriminating beer cans lined up on his amplifier.

He’s too loud on every instrument he picks up. He’s not in sync with how the others were performing. He looks drunk. Towards the end of the gig he is fumbling at a synthesiser. I think he now knows he’s messed up. a chasm opens up between him and the other musicians.

The childish glee we both shared with the sound is long gone. And now we are both worried and alone.

I think about leaving. I’m not sure what to do.

A lady sat next to me said the loudness was “wild” and comments that I didn’t have earplugs in.

I passed some by the entrance. I knew I should have picked them up, but I read that bad ones can do more harm than good, so had been holding out for an expensive pair. And the sponge ones at the door seem to really mess with the sound for me.

I look around to see if anyone else is recoiling. I leave. And seemingly no one else does.

Twenty-four hours had passed, and my ears are burning. As I lay in bed, listening to the rain, I attempt to discern any differences in sound. I shift to one side, pillow cradling my left ear, and noticed a muted quality. The rain’s nuances – the shape of each droplet, the elastic band of sound, the bending pluck, and the pop of the splash – were all lost on me.

Comparing my ears, I perceive my right ear, the one that had faced the speakers to be 50% weaker. Yet, as I reflected on the burning sensation in my left as well. Maybe they are both damaged.

Somewhere in the middle of my head there’s a ringing. The top right. It’s high pitched and sounds like tiny bells chiming at an electric speed. I’ve had ringing before but this one sounds different. It’s bigger and glued into my cortex. It’s feels lodged. I learn there’s different forms of tinnitus, people can hear a buzzing, clicking, hissing, roaring, or rushing sound. But the most common is this ringing. The word tinnitus comes from the latin ‘tinnire’ to ring.

I write this note. A record of the emotion. The tragedy, and the damage wrought. I read that it normally recovers. I’ll have to wait. And listen.

Research offers a glimmer of hope, suggesting that such conditions often recover with time.

The thought of emailing Dr. Kar, my ENT consultant, crossed my mind, but I decided to wait until I could undergo testing in a few weeks. Anticipating an upsetting diagnosis. I couldn’t help but feel a deep affection for my ears, which had always brought me immense joy. I lamented my past negligence, realising too late the importance of protecting them.

I want to go out in the rain and feel its coldness on my face. Even if it would only confirm the diminished sensitivity of my hearing. I crave the sensation. A reminder of the power of touch and feeling. The unfiltered truth. It was raining and I was there. Alive.

I want to go out in the rain and feel its coldness on my face. Even if it confirms that it’s only my hearing that is dimming. I want the sensation. The reminder of touch and the power of feeling.

***

Two weeks had elapsed since my correspondence with Dr. Kar. But there’s no change. I curse him.

Panic drives me to scour the internet for remedies, prognoses, therapies. “Tinnitus is permanent” – each site reminds me. I’m directed to counselling services. I call up hearing clinics but they’re really designed for elderly patients with presbycusis, the name for age related loss of hearing. They didn’t quite understand my need for urgent care. “We like all patients to come in for a clean first, and once the ear has been clearer, we see if we need to book in a follow-up appointment”. I’m 38, and while I’m not adverse to pampering, this didn’t feel like it carried the luxury of a head massage at the hairdressers. It was obvious that these clinics are not set up for acoustic trauma patients. I didn’t need help washing.

It’s 11:30pm on a Saturday night and I’m at the hospital. An out of hours GP clinic has agreed to see me. I’m impersonating one of those terrible patients. Desperate to obtain some medication I’m not quite sure will work; of which I can’t comprehend the side effects, nor whether a prescription is permitted under our healthcare system. Give me drugs, big powerful and terrible drugs. Drugs that would floor a small mammal or break a child out in hives.

Like a bad patient I have found an article online that describes research undertaken on soldiers, in which they were administered prednisolone, an oral steroid, shortly after acoustic trauma. It has proved effective and it’s the only bit of hopeful news I’d read since the accident.

I beg the GP who is not aware of the research and understandably quite frustrated by the conversation. I argue confidently, without any professional knowledge, that prednisolone is taken all the time, and it’s not like I’m asking to inject bleach. The GP consults with an on-call ENT surgeon at another hospital. I imagine the surgeon, roused from slumber, conceding to my request with a mix of fatigue and resignation.

As the GP outlines the potential side effects, including sleeplessness, increased appetite and water retention; mood swings, anxiety, irritability, or depression. Nausea and stomach pain. Headaches and dizziness. She clarifies that these were not so much possibilities, but rather, inevitabilities. Before dismissing me, she remembered to prescribe a medication to mitigate the impending constipation. Somehow I feel like I beat the system. In my own bunged up, objectionable way.

The drugs work. My hearing feels much better. A diet rich in zinc, fish, broccoli, and bananas; abstinence; regular rest; and the diligent use of earplugs when I go near anything fractionally loud. I also avoid TV and music, which exacerbate the tinnitus.

My evenings and weekends are now spent reading, focusing intently on each page as a means of mindfulness. This distraction helps block out the persistent ringing. Despite my progress, Dr. Kar’s prognosis lingered: my condition was likely permanent. No more music, no more concerts. My ears had a good run of it. This is going to be the start of a new phase in my life. – one of acceptance, literature, and quiet pursuits. I had already experienced a lifetime of music; now, it was time for something new. I don’t know if this is sustainable but I have no choice. It has to be.

I secured an appointment with an audiologist, eager to explore the possibility of further steroid treatment. In my mind’s eye, I envisioned my ears, like Hulk Hogan, jacked and excited. Fearless and unnaturally eager.

I was ready for the clinical truth. No matter how bad it was, it had been much worse.

Jane the audiologist is lovely. I feel it’s partly her nature and certainly what makes her great at her job. I can feel the sensitivity of the situation – staring down a potential lifetime of damaged hearing and endless ringing.

The thought that I’ll never again get a moment’s peace. There’ll always be this noise. I remember the articles about depression. Those that never recover from the psychological trauma. As a man in my 30s, suicide is the biggest killer and I feel it prowling. In her kindness and carefulness it feels more present. Like for the first time the shadow has taken a material form. My anxieties are like an electricity. Fizzing away, invisible but undeniably present.

I make lighthearted jokes and recall the incident like I was on a TV chat show. Affable and euphemistic. It feels like a performance. But Jane who is sweetly cynical, doesn’t believe any of it.

What’s nice about this meeting is that I don’t feel like I need to sell my anxieties. In a way that it would need to be established with someone else.

When you tell someone that you’ve lost some hearing and now have an endless ringing in your ears, you can see the delay in reactions. You know people understand that this is a bad thing, a raid on quality of life, a robbery of music as pleasure.

We discuss the steroid treatment. Jane rattles her fists in celebration. She on my team. “No one knows they work.” She elates. ”…and?” They work. “Fantastic. Right let’s see how you measure up.”

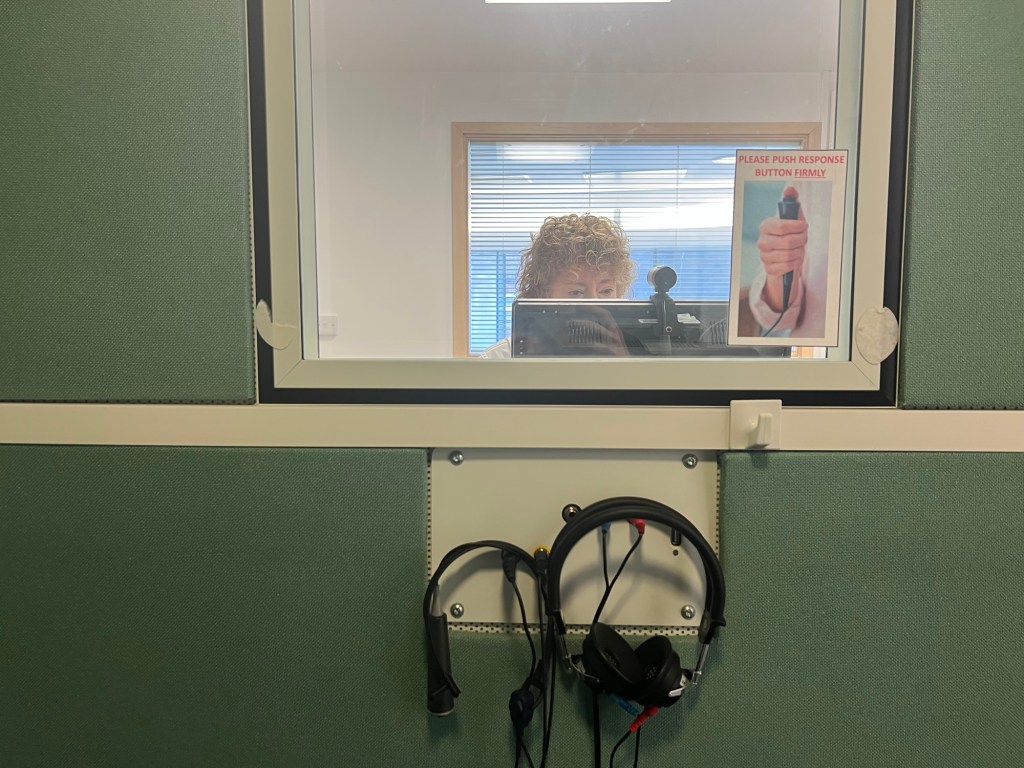

The examination, for those who have not experienced it, is appropriately practical, sat in an isolation room. With headphones on trying to listen out for feint sounds played through other ear. A chord with a buzzer. “We’ll have to stop if someone uses the lift.”

The room is a mix of a pastel woven baize coated on sound absorbing boards, mixed with laminate strips. There’s an economy to the room’s design, inherited from a 70s a TV set.

With the headphones set up for just one ear, I press the buzzer when I hear each sound. But then you that to hear the trace of a sound, and it’s hard to know if you’re imagining the note or whether it’s your other ear that’s picking up the frequency. What should be a simple activity fast becomes a complex game of double guessing my own hearing. Did I hear something quiet, or am I imagining it. I’m wondering if my own internal thoughts have a decibel level.

Jane is aware of this internal process, and started to play the sounds with an atemporality. The pause between notes changes, become arrhythmic. It’s to throw you off the “echo” effect as Jane refers to it. The echo being the gap between the sound as played and your brain imagining it anew. I didn’t expect this kitsch clinical space to house so much psychedelia. Or for this sweet lady to engage in a mind bending game of cat and mouse.

I return for the same test again. Jane can tell that the prednisolone significantly improved my hearing. It’s almost like the way I hear noise reveals a scar. In taking the test she can see the healing and the repair. She points to where she thinks it had been. Way down the chart into an area that would require hearing aides. I’m thinking about how kind she is, and whether she’s just saying this to make me feel better. Maybe she’s applying her professional intuition. I remember that the prednisolone seem to have worked, I remember that I did notice a significant improvement.

The tinnitus is three fold in my right ear. Two lower frequencies and a very high one. The chart maps out the hearing loss in graphic form. Jane points out that it’s just a portrait of where my hearing is today, and over time it will change. I think I was focussing on the tinnitus and not really appreciating the extent of the loss.

We move on to the next assessment, a fax machine looking thing that measures my inner ear pressure, a tympanogram. My right ear has an abnormal level of negative pressure which is amplifying the tinnitus and obstructing my hearing. I will need to wait to see if it corrects itself, or if my ear drum needs to be pierced to recalibrate the pressure.

News of permanent hearing loss in one ear and to see it on a chart has really fucked me up. But I do know that I have had trouble hearing my girlfriend, when we’re talking. And I was hoping or at least thinking that it would be temporary. But I hadn’t really accepted that I was in so much trouble.

Am also shocked because I’ve not been listening to my TV or stereo because the music wasn’t sounding right at all, and I knew I’d taken a hit there. Maybe I thought it would recover.

I’m also surprised by how well the hearing in my left ear is doing. It’s nice to know that it’s still performing to a reasonable standard.

I’m also reflecting on that what I can hear now, it could improve following further treatment.

It’s just that I’m reflecting on the news of the loss. Thinking that the chart is my future reality, when there’s also news that it could improve and half the damage.

I think of the band, I wonder if I should let them know what has happened. Are they even aware they were involved in an accident? I’d been looking on the comments sections against posts by the promotor. I’m waiting for a public apology, I wonder if anyone else is suffering like me. I email the promotor who passes me on to the venue. I was the first and only person to come forward. Have I just been that unlucky.

***

What follows is a mental decompression. The fear of further damage or exposure reduces of time and I’m less worried about causing more lasting damage from daily activities. I decide to not wear my earplugs on the tube for the first time. I attend a concert with a small group of singers, unamplified.

I start to manage the tinnitus. It comes and goes now, as I become distracted. It’ll be a journey for my brain to adjust to my new ears. As Jane explained, the brain notices a drop in hearing so “turns up the gain” and that’s what creates the tinnitus, the brain trying to locate the missing signals. I know I need to relax and distract myself. I know the ringing will go away if I focus on other things. I will adapt. I need to gradually expose my ears and retrain my brain.

It’s mid December and I’m at home, playing music from my stereo: ‘grounation’ by Count Ossie and The Mystic Revelation Of Rastafari. For the first time I can relax into the sound. My hearing doesn’t recoil away from the notes and shut it off like it had previously. To tones started to feel familiar, not restricted and tight but cogent and flowing. It was like the music I could remember. I weep on my sofa. The feeling that music is still there, a quiet chorus, waiting for me.

Image taken by the author at the audiology clinic.