In 1615, an illiterate widow named Katharina Kepler was accused of being a witch. Her neighbours in the town of Leonberg claimed she had poisoned a woman with a bitter potion, consorted with demons, and appeared in dreams as a cat. At sixty-eight years old, she was arrested, imprisoned, and interrogated. She was chained to the floor of a cell for more than a year. Her prosecutors were confident: there had been omens, stories, suspicious herbs. The logic was, in its way, complete. A woman alone in her old age must have power; if she was not blessed, she must be cursed.

The only reason we know anything about this story let alone remember Katharina Kepler’s name is that she was the mother of Johannes Kepler, imperial mathematician to the Holy Roman Emperor and one of the founding figures of modern astronomy. Kepler personally mounted her defense. He poured over case law, studied procedural loopholes, and wrote a 128-page legal rebuttal dismantling the charges. After six years of proceedings, torture, and incarceration she was released. She died six months later.

Her son Johannes Kepler believed that the orbits in our solar system followed harmonic ratios akin to musical intervals. A revival of an ancient Pythagorean idea of celestial harmony. He believed the planets emitted musical tones based on their angular velocities. This attempt to write a cosmic symphony would be brought down to earth in 1666 by Newton’s laws of universal gravitation.

We are always looking for patterns. We project them onto markets and politics, we see faces on moons. Referred to as apophenia, it is our greatest cognitive talent and our most dangerous vulnerability. It explains why we invented gods, charts, conspiracy theories, and musical notation. It explains why we expect songs to resolve, melodies to repeat, stories to arc toward meaning. It explains why so much experimental music sounds, to the unprepared ear, like a mistake.

This inclination serves us well (most of the time). But there are artists who test its boundaries. Musicians, especially, who explore the liminal zone where randomness flirts with structure, and where structure starts to dissemble. In the twentieth century the composer Iannis Xenakis used stochastic processes to generate vast clouds of sound. These were forms of control masquerading as disorder.

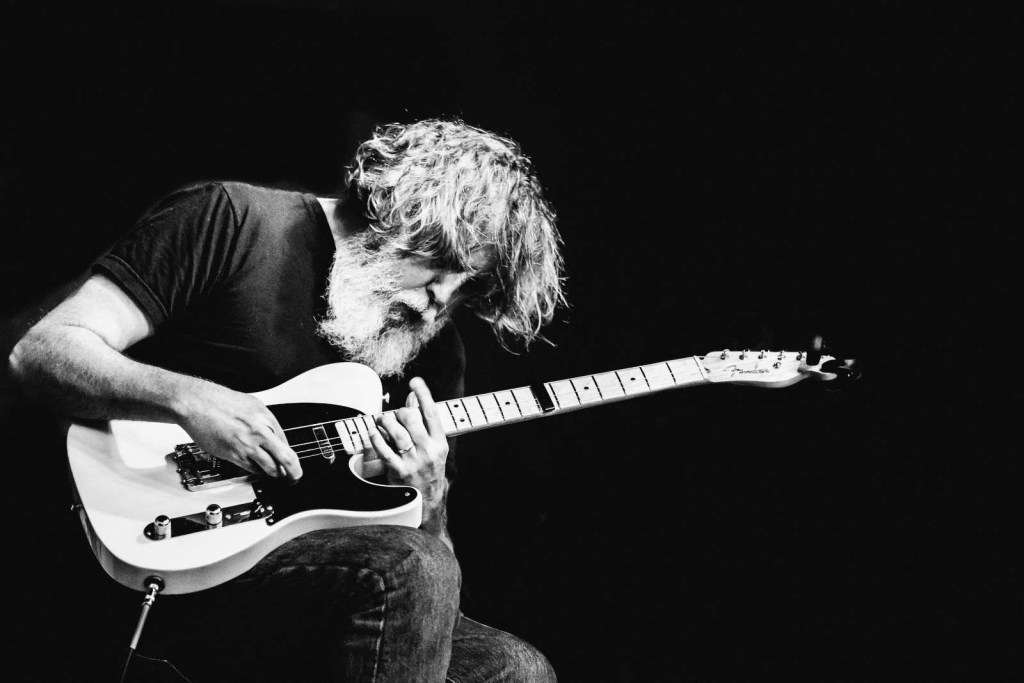

The most common misconception of Bill Orcutt’s music is that it’s freeform or improvised. That the integers between notes, which can be sizeable, are bold gambles made in the heat of the moment, compelled, possessed in his craft.

While his music is fauvish, it is mathematical; abrupt yet refined. It sounds like a rebellion against form but really it’s projections of a meticulous imagination. The freedom you hear isn’t the absence of discipline. It’s the reward of it. We hear chaos when there is order, witchcraft when there are patterns. His music defies one of our most human abilities.

Orcutt begins with breaking something and then builds a system around it. To restore order and test how much form can survive from rupture. I imagine the challenge that Kepler found himself undertaking, defending his mother against a broken judicial system, is in fact the one that Orcutt sets for himself.

For much of the 1990s, Orcutt and his wife performed as Harry Pussy, a noise duet that married punk provocation with experimental rigour. Their records were fast, feral, and splintered, half-obliterated manifestos of a scene still in the process of inventing itself.

The band embraced obliteration. Their live sets were legendary for being loud, fast, and short, brutish in their approach. There were no solos. There was no center. The songs started and ended like detonations. What carried over from that phase into his solo work wasn’t the volume or the speed, but the method: build a set of conditions, strip away the frills, and see what can survive.

In 1997, following the dissolution of both the band and his marriage to drummer Adris Hoyos, Orcutt left music. He began coding. He raised a family. For nearly a decade, the man who had helped stretch the idea of guitar music to its most dissonant ends made no recordings at all.

When he returned in the late 2000s with A New Way to Pay Old Debts, it was with an acoustic guitar that seemed barely able to contain its own sonic vocabulary. The four-string tuning offered new freedoms, a limitation he embraced decades earlier when a broken guitar became his only tool. It invited angles. The melodies stuttered, looped, collapsed. They pulsed with something old, blues guitar, but frayed at every seam. The album was a recalibration, not a comeback. Orcutt had not resumed where he left off; he had re-wired his system.

He adopted a half-broken acoustic guitar with only four strings and recorded straight to tape, sometimes with the mic so close you could hear his fingers slipping on the frets. The music is raw, but not careless. Each note arrives with attack and intention, then vanishes. It’s a kind of minimalism, but less serene than its classical forebears. If La Monte Young asks you to sit still for an hour inside a sine wave, Orcutt asks if you can stand thirty seconds inside a shattering chord.

That’s the paradox. The music sounds violent, improvised, random. It isn’t. Orcutt composes in fragments, short lines, odd rhythms, offbeat tunings and then layers them with mechanical clarity. It’s a mathematics of rupture. You hear the sound of a person testing limits not in what can be done, but in what ought to be done, aesthetically, structurally.

He has said he doesn’t care much for gear. His four-string guitar isn’t an artifact of fetishism, but of refusal. He limits the instrument the way a poet might limit the meter or form, because constraints are how new languages are born. In the absence of six strings, he finds a new syntax. Not simpler just differently ordered.

That sense of music-as-system reached a new dimension in 2015, when Orcutt released Cracked (full title: i_dropped_my_phone_the_screen_cracked), an open-source programming environment for live sound synthesis. The interface is deliberately sparse: no knobs, no sliders, just a blank window in which to write code. Typing is composing; syntax becomes signal. You don’t just play the instrument you build it, one line at a time. For Orcutt, it was a logical extension of his practice: a way to reframe the guitar’s erratic intimacy in computational terms.

Cracked, is publicly available and licensed under MIT. It’s a minimalist JavaScript library designed for live audio synthesis via method chaining, evoking CSS-style selectors, and intended for creative coding within a browser or app environment.

The program operates on a declarative syntax: __() creates a sound source (e.g. sine, square, noise), to which chainable modulators (LFOs, filters, delay, gain) can be attached, each modulating another element’s parameter.

Far from being chaotic or arbitrary, Cracked’s architecture reveals Orcutt’s commitment to improvisation as structured exploration. Each snippet is freeform: the coder chooses oscillators, LFOs, waveforms, and routing. Yet the environment demands consistent syntax and signal flow, guiding the performer toward coherent sonic outcomes. The interplay between the freedom to invent and the constraints of the system is central to how Orcutt thinks about improvisation in both his digital and guitar-based work.

In The Anxiety of Symmetry two 15-minute improvisations are built from six female voice samples, each describing list positions (“one,” “two,” etc.) pitched to correspond with scale degrees. As these loops cycle together, their differing lengths and tunings generate syncopation, polyrhythm, harmonic drift. The piece is placid on the surface, but structurally obsessive reflecting Orcutt’s interest in human fixation with symmetry and order-in-disorder.

These pieces are open-form: the code defines the rules, durations, modulation sources but how they evolve depends on the performer’s choice of values, timing, and interaction. They feel improvised because the code runs live but they remain distinct from unbounded chaos because each configuration is compositional.

These albums are conceptual works as much as musical ones. In A Mechanical Joey, the Ramones’ frontman counts off eternally (“One, two, three, four!”), his voice looped and modulated until it becomes rhythm, then texture, then punishment. The piece is equal parts dadaist prank and algorithmic étude. The score is the source code. The aesthetic lives in the absurdity of its execution, but the method remains precise. Orcutt composes like a technician: revise, rerun, recode.

Throughout Orcutt’s work there is a persistent interest in the conversation between form and freedom. Some albums repeat older ones. Others return to discarded ideas, rebuilding them with new tools. The discography behaves like a single, sprawling meta-composition, one long feedback loop between instruments, programs, performers, and performance. It is not a retrospective so much as a recursive archive. Every record documents a moment of thought in motion.

This is, perhaps, what makes Orcutt so singular. He is not simply an experimental guitarist, or a noise provocateur, or a programmer with a musical bent. He is, above all, a practitioner: someone for whom music is a way of working through problems, whether in harmony, hardware, or code. His compositions are blueprints as much as expressions. His albums are byproducts of method, but never reduced by it. If his music feels free, it’s because it’s been built to allow for freedom.

It’s experiment. Not the romantic, finger-painted version of experimentation, but the laboratory kind: controlled conditions, calibrated tools, ruthless observation. The kind where you ask: What happens if I move this one element, and leave the rest untouched? The work of comparing—measuring, testing, adjusting—is paired with an aesthetic that feels, in a word, fauvish: untamed, bright, startling, unrepentant.

Take Music for Four Guitars. The material is short (fourteen pieces, all under three minutes) and built from repeating fragments. On first listen, they sound like mining exercises: each riff boring into the same vein of rock from slightly different angles, vibrating near each other in unison. You feel the vibrations before you hear the intent. The voicings are staggered. The shapes repeat with subtle mutation. It is not improvisation, but variation. Precision masquerading as frenzy.

The word “experiment” tends to get overused in art, especially when what’s really meant is “incomplete” or “accidental.” That’s not what Orcutt is doing. He’s demolishing, again and again, from different angles, until he sees how it breaks. And then he uses the fracture to create his own cosmic order.